Pre-Season Conditioning: Big Yes or Big No?

Pre-season tends to bring out the worst of our misunderstandings around conditioning:

“We play so very slow - we need to condition more!”

"You lot look exhausted - we need to condition more.”

"Our opponent played 3x faster than us and tore us up - we need to condition more!”

While it may, on first glance, appear that the source of all these problems are a poorly conditioned team, I encourage you to take another peak and consider the possibility of a lack of speed, an ineffective system of play, lacking technical or tactical ability or knowledge, and even poor nutrition may also be contributing.

Slow or Fatigued?

A slow player and tired player are two different animals.

And, although they are common complaints in football, they are not the same issue.

Speed and endurance have different fuel sources, as well as different mechanisms and systems that influence them.

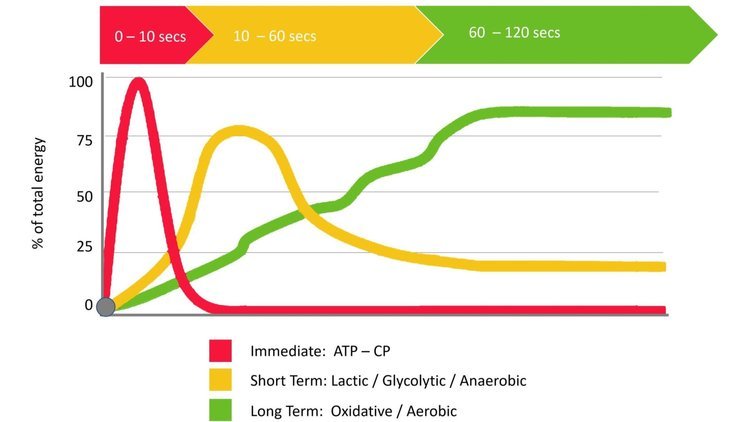

For sprinting, changes in direction, and other explosive bursts on the field, the phosphagen system (ATP-PC; System 1) and the anaerobic glycolytic system (System 2) are primarily engaged. Utilizing stored ATP and creatine phosphate, the ATP-PC system provides immediate bursts of energy for short, intense efforts. The anaerobic glycolytic system, kicks in for slightly longer bursts, breaking down stored glycogen into ATP without requiring oxygen. These systems collectively contribute to quick, repeated accelerations and rapid movements with breaks in explosiveness between, which are essential for football.

Endurance, on the other hand, calls upon the oxidative or aerobic energy system (System 3). This system relies on the availability of oxygen to produce energy through the breakdown of carbohydrates and fats. It is the key for maintaining a consistent performance level (think: tempo without skill or speed deterioration in the 2nd half) over the duration of a match. Football players need a well-developed aerobic system to sustain continuous running, frequent changes of pace, and prolonged efforts throughout the game.

So, again, these two fitness qualities are two different beasts, although they present similarly and are easily confused - even by experienced coaches.

A team that plays at a lower tempo throughout a match and struggles to keep up with high-tempo opponents is most likely severely lacking in speed capacity - literally the ability to run fast, the capacity to even hit a maximal velocity of over 25 km/h.

(To learn more about how expanding a team’s speed capacity can put them ranks above their opponents, peep this video on the Aerobic Speed Reserve.)

A team that develops clear signs of fatigue by the 70th minute and begins suffering the deterioration of tempo or skill execution has a conditioning weakness, not a speed problem.

Breakdown of Speed & Conditioning Demands

Differentiating between speed and endurance is the first step in being able to train each fitness quality most effectively. Knowing what you are training and how to train it are less common than we think. And knowing the basic principles of the Anaerobic Speed Reserve can help here immensely.

SPEED

There are two types of speed demands relevant to football.

Maximal Speed: also called “maximum velocity” or “top speed”, this is a player’s absolute speed capacity over 30-60 meters. It is not possible to reach one’s highest gear before that, and it takes significant training to hold a top speed for more than a few additional seconds after reaching it - in general, the top speed will have already deteriorated between 40 and 80m. It is worth purposefully investing in MaxVelo training, because a team who comfortably plays at 19 km/h and simply does not have the capacity to run over 25 km/h is going to deteriorate rapidly in a match against a team who plays fluidly at 21-23 km/h.

MaxVelo can be trained 1-2 a week with repetitions of 30-40m sprints. As a football field is only so long, true 60m linear sprints are rare in matches, so shortening the distance is still an effective training modality. Research and practice over the last 5-8 years show improvement with just 3-5 repetitions of 30m sprints twice a week, with sufficient rest between to fully recover the athlete’s aerobic system between bouts.

It should also be noted that it is not possible to achieve an actual maximal sprint with a ball at your feet. The data suggests we can reach up to a reliable 80% of top speed with a ball, but that is submaximal and does not contribute to widening that top speed capacity. Leave the ball away for a few reps a week - that will not kill you (or your athletes, no matter how motivated by football they are - I am hypothetically staring into the soul of German Football right now as I write this. Why would you write a game situation with a ball in order to get in your sprint volume when… you still will not reach MaxVelo and it takes significant time as opposed to 10-15min?)

Acceleration: this is the critical phase of gaining as much speed as possible over a short distance. We often consider acceleration as only relevant to “the first few steps” and, although an athlete definitely accelerates violently in the first 5-10m, acceleration takes place all the way up until maximum velocity is achieved (up to those 30-40m)!

The skill of rapid, effective acceleration is crucial to football because that’s the majority of most positions: accelerating, decelerating, changing direction or taking on a ball, reaccelerating, scanning the field, slowing down, and the sprinting again. Repeated accelerations over 5-10m is the bread and butter of this game.

Acceleration can be trained weekly. It is significantly less exhausting than maximal velocity sprinting, even though these repetitions should be completed at 100% effort as well. I start new-to-speed-training players with 10x10m sprints with 1min rest between sets, adding in 20s by week 2 or 3 and gradually increasing volume while maintaining rest times. It can be trained with many other factors involved: deacceleration, reacceleration, change of direction, taking on the ball, from a different position (laying, turning, backwards run, high knees, side-shuffle, push-up position…) and is easy to adapt into training sessions.

Regeneration: As a rule, speed training requires 1min of rest per 10m of distance covered a maximal (90%+) effort. For a 10m acceleration, that is one minute of complete rest. for a 50m sprint, that is five whole minutes. It seems long, yes, but it is worth building into the program if what you actually want are results and not just another conditioning session that leads to deterioration of speed and pulled hamstrings very, very fast.

CONDITIONING

Again, there are two types of condition that are critical to this sport.

Baseline Endurance: players with this type of endurance (Grundausdauer 1 in German) are aerobically more efficient and will find many actions, skill executions, and even some sprints to be more efficient and require less energy than players with a lower baseline. These athletes can maintain of a low yet steady tempo and relatively constant pulse over time without noticable deterioration in skill or speed.

The good news: this type of conditioning is easy and quick to improve - within 3-4 weeks, a difference is visible. This baseline can be raised by conditioning according to Heart Rate Zones 1 and 2: pulse should remain low (generally under 130bpm for youth and young adult athletes) and relatively steady, with no sprints or tempo changes over the duration. It is difficult to remain in the lower zones while running, even at a slow jog, so I highly recommend players bike or row for 20-35min in Zones 1 and 2.

Admittedly, I used to be strongly against baseline conditioning in the pre-season, because (and this remains true!) in the best case scenario, players get sufficient baseline work during their team training sessions. However, depending on the playing level, the league table or tournament groups, and fitness level in general (think rehab status: a player coming off an injury needs to be doing baseline in rehab!), this is sometimes not sufficient to get all players sufficiently metabolically fit for the team’s playing system or opponent style of play. I have fit players do more baseline conditioning on a case-by-case basis, if team training turns out to be too little to get a metabolic adaption.

Tempo Running/Repeated Sprint Ability: “football is a game of repeated sprints, not a long, slow jog” definitely hits the nail on the head! This sport is full of high-intensity running bouts (these are submaximal sprints at under 90% of top speed!) that spike the pulse suddenly with breaks for quick recovery between bouts. Meet Repeated Sprint Ability, the best friend of any coach in the pre-season.

I start players off with tempo runs to the tune of 6-10 runs of 100m with 60-90sec break between. This is a noticeable reduction in rest time compared to speed training, which would require 10min of rest after a 100m full out sprint effort. The goal here is to induce a faster recovery, to force the body to become more efficient in fulfilling our energy needs. Once athletes are adapted to this, we can introduce RTP protocols, usually involving 20-40m sprints with 30-45sec rest between repetitions. There are dozens of RTP protocols, but be sure to adapt the rest times, distance, and total volume to what you or your team need, not just randomly reducing a rest interval because it seems too long.

The primary goal of building up both of these condition-based fitness qualities is to acquire more resilience against fatigue (RTP) and adapt to an economic process of managing fatigue with no fitness depreciation in the lower HR zones (baseline training). Here we learn to control fatigue - and our reaction to it!

Sample Training Week

This is not the Best Training Plan Ever, just a basic example of what a week might look like with these factors built into or in addition to team trianing in the pre-season.

Monday: Accels (5 reps) + Max Speed (3-5 reps) at the start of Team Training

Tuesday: Free, Whole-Body Strength + Mobility

Wednesday: Team Training + RTP (8x30m w/45sec) at the end of training

Thursday: Baseline Conditioning (30min bike) OR Free

Friday: Team Training + Upper Body Strength

Saturday: Test Game

Sunday: Free + Recovery/Mobility

I hope this helped you better understand the energy systems and the different in speed and conditioning fitness qualities, and maybe even a bit about how to train them. Conditioning in pre-season is not an overwhelming yes or no - it entirely depends on what you and your team need to succeed. In the best case scenario, you do not need extra baseline conditioning in the pre-season, but RTP and speed will most likely be keys for most of the competitive year.

As a rule, I generally avoid specific practical recommendations (sets, reps, frequency) because there are no two athletes, two teams with the same set-up, same needs, and same fitness level. Do what you can with what is here - there is much more floating around online, be careful! - and try to adjust it to whoever you are training as best as possible. Someone else’s workout brings no one results.

Avoid focusing too much on conditioning. Don’t overdo it if athletes are thoroughly conditioned via team training and match play. This happens over the course of the pre-season naturally - don’t overload if not absolutely necessary, but give less-conditioned players concrete ideas on how to improve with an extra session per week.

Avoid confusing poor endurance for a lack of speed. They aren’t the same, but they are both critical. Keep them both in the training week in some way - speed ESPECIALLY during the season too, as we begin to lose speed by the 7th day without sprinting. Work toward developing a greater capacity for max velocity and get reps on reps in for acceleration.

Teams who “get there” faster and “stay there” longer tend to win anyway.

FURTHER READING for my fellow nerds:

Arslanoglu, E., Sever, O., Arslanoglu, C., & Yaman, M. (2013, January 1). 10 m and 30m scores of the players with respect to their positions. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/10-m-and-30m-scores-of-the-players-with-respect-to-their-positions_tbl2_316118830

Gualtieri, A., Rampinini, E., Dello Iacono, A., & Beato, M. (2023). High-speed running and sprinting in professional adult soccer: current thresholds definition, match demands and training strategies. A systematic review. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1116293.

Iacono, A. D., Beato, M., Unnithan, V. B., & Shushan, T. (2023). Programming high-speed and sprint running exposure in football: beliefs and practices of more than 100 practitioners worldwide. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 1(aop), 1-16.

Kilen, A., Hjelvang, L. B., Dall, N., Kruse, N. L., & Nordsborg, N. B. (2015). Adaptations to Short, Frequent Sessions of Endurance and Strength Training Are Similar to Longer, Less Frequent Exercise Sessions When the Total Volume Is the Same. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research / National Strength & Conditioning Association, 29 Suppl 11, S46–S51.

Meckel, Y., Einy, A., Gottlieb, R., & Eliakim, A. (2014). Repeated Sprint Ability in Young Soccer Players at Different Game Stages. In Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Vol. 28, Issue 9, pp. 2578–2584). https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000000383

Pivovarniček, P., Pupiš, M., Švantner, R., & Kitka, B. (2014). A Level of Sprint Ability of Elite Young Football Players at Different Positions. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 4(6A), 65–70.

Shah, S., Collins, K., & Macgregor, L. J. (2022). The Influence of Weekly Sprint Volume and Maximal Velocity Exposures on Eccentric Hamstring Strength in Professional Football Players. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10080125